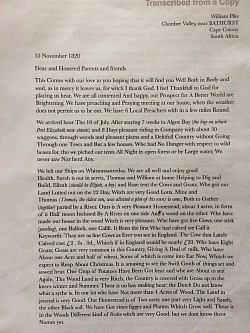

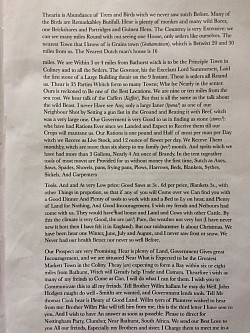

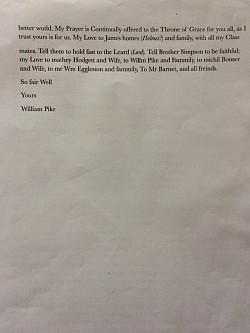

" ADVERSITY SEEMS TO STREGTHEN THEM "

An optimistic letter written in November 1820, 4 months after arrival

The transcribed letter by William Pike which follows, describes conditions at Clumber a few months after their arrival. The tone of the letter is very positive and upbeat and William extends an invite for the recipients to come and join him in conditions which he considered far better than in England.

One of the reasons for the positive tone of this letter was that the 1820 Settlers arrived just after good rains so the countryside was looking magnificent, as the current Eastern Cape can, with tall green grass and flowering trees and shrubs.

What they only realised later, was that unlike England, the rainfall pattern was vey erratic and could not be regarded as given.

And those pleasant and verdant conditions were to change drastically in the following few years due to rust in the wheat crop, drought, and severe flooding in 1823.

Settling Down to Become Farmers

The first few years were nothing like a walk in the park. A new land, new weather patterns and, for most, a new vocation of earning a living from the land.

What happened to the overall group of 1820 Settlers after their arrival ? Moving away from the Nottingham Party in particular, let us consider for a moment what the entire group of roughly 3800 Settlers had to endure.

Firstly, we have to understand that there were restrictions in place. They were not allowed to move from their locations unless they had a pass.

Secondly, they were not allowed to hire labour, so all work had to be done either by themselves or collectively as a group.

Thirdly, they were to receive rations for the first two years or so until their first crops were harvested. The cost of those rations was debited against the deposits they had paid. All rations had to be collected at a number of distribution points involving many hours uof walking with no transport provided, to move the goods. And in the case of fresh meat, live sheep were provided and these had to be driven home with many sheep being lost on the way as they disappeared and scattered into bush thickets on the way. Some devised a method of making wooden sleds to transport their rations.

Fourthly, they found out after a time that they were unable to hold meetings to discuss their grievances.

Fifthly, there were no roads available to them to move easily from point to point.

Lastly, there were no towns or infrastructure available to support their needs. Grahamstown and Port Elizabeth were merely military outposts and Bathurst was simply a distribution point for rations.

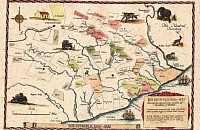

What they were not aware of, was that they were placed on the Eastern Border to be a buffer against incursions by the Xhosa into the Cape Colony, across the border of the Great Fish River.

The area that was allocated to them was virgin land, covered with trees, bush and scrub. Laboriously the land had to be cleared, tilled and planted. Kraals had to be built. Homes had to be constructed as the tents they were supplied with, could not last indefinitely. The first houses were made of wattle and daub, stout corner posts with a lattice of willowy stems woven between, and covered with mud. Door and window openings were covered with a sail cloth which could be lifted to let in the light or lowered to keep out draughts. Most of the land which was cleared for the new fields and orchards as well as the houses, were located close to the water source, a small stream. All credit to the settlers that by the end of 1820, small fields were planted and the crops of wheat looked so promising, most were astonished at the rate of growth . Then disaster struck. Throughout the colony the wheat shriveled and died due to a condition called rust. Unknown at the time was that the seed they planted contained the causant factor of the condition called rust. Undaunted in 1821 they planted again, only to achieve the same result, rust. As is usual for this district, the weather patterns can never be considered stable. When they arrived in 1820 the countryside was looking beautiful and lush thanks to the rains that had fallen. In 1821 that rainfall was disrupted and they started entering a period of drought. The wheat crop shriveled due to rust, again, and died, and the fields were parched. Even the milk cows dried up. Things were starting to look desperate. Conditions worsened again in 1822 with another wheat crop failure and continued drought. Then in October 1823 the rain came, and it came in such torrents that it washed away most of the fields that had been laboriously cleared, as well as the wattle and daub houses. The quiet little rills and streams became raging torrents and cleared everything in their path. It is recorded that in the first week there was gentle rain, the second week was torrential downpours and in the third week just sporadic showers. The Great Flood, as it became known, was the final straw. By now their clothes were in tatters , most were walking barefoot, hats were made of plaited palm fronds. Clothes were the same they arrived in and were either repaired or completely made from the remnants of their canvas tents. Many were starving, with bread being totally unavailable due to the collapse of the wheat crops over the years. The reports which were coming in to a Society in Cape Town, called the Relief for Distressed Settlers, were heart rending and in no way are events over dramatized here. Most settlers were in a state of penury. All were affected. Even those with means reported that they had lost everything and were wondering where the next meal was coming from. Clothing, valuables, even blankets, were reported as being sold to raise cash.

One report, and one report only, will I mention here so as not to belabour the point - and it can be used as a barometer for what the conditions were really like. A lady, "confined in child-bed" was discovered in her home. In the same room was her husband , lying dangerously ill. The previous day she had buried her child in the garden. They had not eaten for two days as there was no food. They were starving. The officer who discovered them assisted them as best he could. The Landdrost in Grahamstown, Henry Rivers, disregarded the report and did nothing to alleviate the plight of this poor couple.

At this time, with the appalling physical conditions the Settlers now found themselves in, a no less calamitous event occurred, a series of political attacks on them by none other than the Governor, Lord Charles Somerset. At the time of the 1820 Settlers' arrival, Lord Charles Somerset, the Governor of the Cape Colony, was on leave in England. Sir Rufane Donkin was Acting Governor in his stead. Donkin showed real concern for the Settlers and tried to "make things work" . For example he decreed that Bathurst become the administrative centre rather than Grahamstown as the vast majority of Settlers were congregated in this area. He appointed Major Jones as Landdrost of Albany, a successful appointment, as he demonstrated his willingness and expertise to resolve issues. Donkin also pursued the option of opening a port in Port Alfred to open up a gateway for the the flow of materials and produce for the district. He also eased the "lockdown" and relaxed the pass system which enabled those who had a trade and who realised they would not be able to successfully farm, to seek employment or to start their own businesses. One of the major drawbacks of placing this large body of people in this area was there were no towns or villages to support them. There was no established infrastructure. Grahamstown was not really a town, merely a military outpost. Algoa Bay was the same. Bathurst was a fledgling village which stagnated when Somerset overturned Donkin's plans. All credit to those who migrated to these outposts that they eventually created working towns of substance through which goods and services began to flow. Others migrated as far as Cape Town and Graaff Reinet and still some returned to England.

At the end of 1821 Lord Charles Somerset returned from England and resumed his duties, based as usual in Cape Town and far removed from the area where most of the Settlers were placed. Incredibly, despite reports coming in of the problems which had surfaced on the border of the Colony , he only visited the area in 1824. However, he set about undoing most of that which Donkin had implemented. Major Jones, an effective Landdrost was replaced by Henry Rivers who proved ineffective and was viewed as incompetent and uncaring. Expansion of Bathurst was halted when Grahamstown was reinstated as the administrative Centre. With the volume of people deserting their land allocations, Somerset's objective of creating a stable, heavily populated border, evaporated. The settlers meanwhile had other problems which they wanted to discuss at a public meeting but were forbidden to gather by the Landdrost, Rivers. Somerset, on hearing of the proposed meeting, attacked the Settlers by labeling them radicals in a letter to Earl Bathurst, the Colonial Secretary in England. The organisation to refute these accusations was the Relief to Distressed Settlers fund. Also based in Cape Town , they had regular reports coming in to them based on actual visits to the district. They also used Rev William Shaw ( the government sponsored Wesleyan clergyman of Hezekiah Sephton's party at Salem) as a conduit for dispersing funds and goods to those in dire need. So they had a very good understanding of the conditions the Settlers were in. Such was the feeling of the Settlers that they decided to write directly to Earl Bathurst, bypassing the Governor, and setting out their grievances. The paper, dated 10 March 1823, was signed by 171 prominent persons. Their main grievance was the autonomous control of their settlement which was vested in a single individual and they had been denied any means to have their grievances aired and addressed. This resulted in a board of inquiry being set up and from this inquiry it was found that the settlers were in fact, in dire straits, and their needs were not being addressed.

Then another red light began to flicker. Incursions from across the border began in 1821 and unfortunately the first deaths of the cattle herders , two small boys, occurred from these incursions. As the shift in emphasis of the lands from agrarian to pastoral started and the herds of livestock increased, so did the cattle raids. Substantial livestock losses resulted ( 2590 cattle were stolen in 1822 and only 778 recovered) . The protection provided by the military to prevent these incursions proved inadequate and was thinly distributed along a very lengthy, wooded border which provided many hiding places in the dense bush and ravines.

Depredations of the flocks of sheep, herds of cattle continued to be setbacks for the 1820 Settlers . The raiding of livestock reached epidemic proportions following the 6th Border War of 1834. In the diary of Elijah Pike he lists the losses incurred as follows :

5715 horses

111,930cattle

161930 sheep and goats

Besides these losses, 436 houses and 58 wagons were set on fire, 300 houses were pillaged and gardens and standing crops were entirely destroyed. We talk rather glibly about the effects of the Border Wars but these numbers illustrate in this one War the huge losses these indomitable people had to endure and overcome.

Despite the succession of setbacks, the Settlers with true grit, determination and faith, gradually improved their living standards and started investing in their future . It is nothing short of astonishing that at Clumber, the Nottingham Party, paupers at the time of emigration in 1820, erected their first Church at Clumber in 1825. This despite the setbacks they had experienced over these 5 years. All contributed to the construction of the Church by providing labour and materials. They erected their Church on Mount Mercy where they had held a Service of Thanksgiving on their arrival 5 years previously. The erection of the Church was in accordance with the Articles of Agreement all had signed in England, whereby a place of worship and an area for recreation and a market be provided at their location. These areas are still set aside to this day.

REMINISCES OF AN 1820 SETTLER

During a lecture to mark the 50th anniversary of the landing of the 1820 Settlers, Henry Hare Dugmore, a Settler himself, reminisced about the places of shelter the Settlers devised after the wagons departed and left them all alone on virgin ground.

These people left behind established homes with roofs and walls providing more than adequate shelter against the elements. The only shelter they had on their allotted ground were the tents which were supplied on landing in Algoa Bay, the cost of which was debited to their account. Naturally the canvas material would not last long and they had to, as a matter of urgency, erect places of shelter.

So, what did Henry Dugmore have to say about these dwellings? This forms part of his lecture which he presented in 1870:

‘As to the first dwellings themselves, they were of very various and very original orders of architecture. A young brotherhood of bachelors built for themselves a booth of leafy branches, after the manner of the Israelites of old. An economist of materials dug his house out of the bank of a river. The wattled framework of two or three square rooms looked, in the eyes of some, like the founding of a mansion. Many a father and son, with axe on shoulder, ranged the wooded kloofs in search of door-posts and rafters; and many a mother and daughter cut wattles and thatch nearer home for walls and roof; aye, and many a back arched under successive loads, borne toilsomely from tangled thicket and rushy swamp. Stone and brick were among the visions of an advanced order of things belonging to the future.’

(*Henry Hare Dugmore (1810–1896) was an English missionary, writer and translator. He was born in England to Isaac and Maria Dugmore and baptised in Birmingham on 5 June 1810.[1] The family emigrated when his father was financially ruined after being forced to pay the debts of a relative for whom he had stood surety. The Dugmore family sailed to South Africa on the vessel Sir George Osborn in 1820 as part of the Gardner party of 1820 Settlers.)